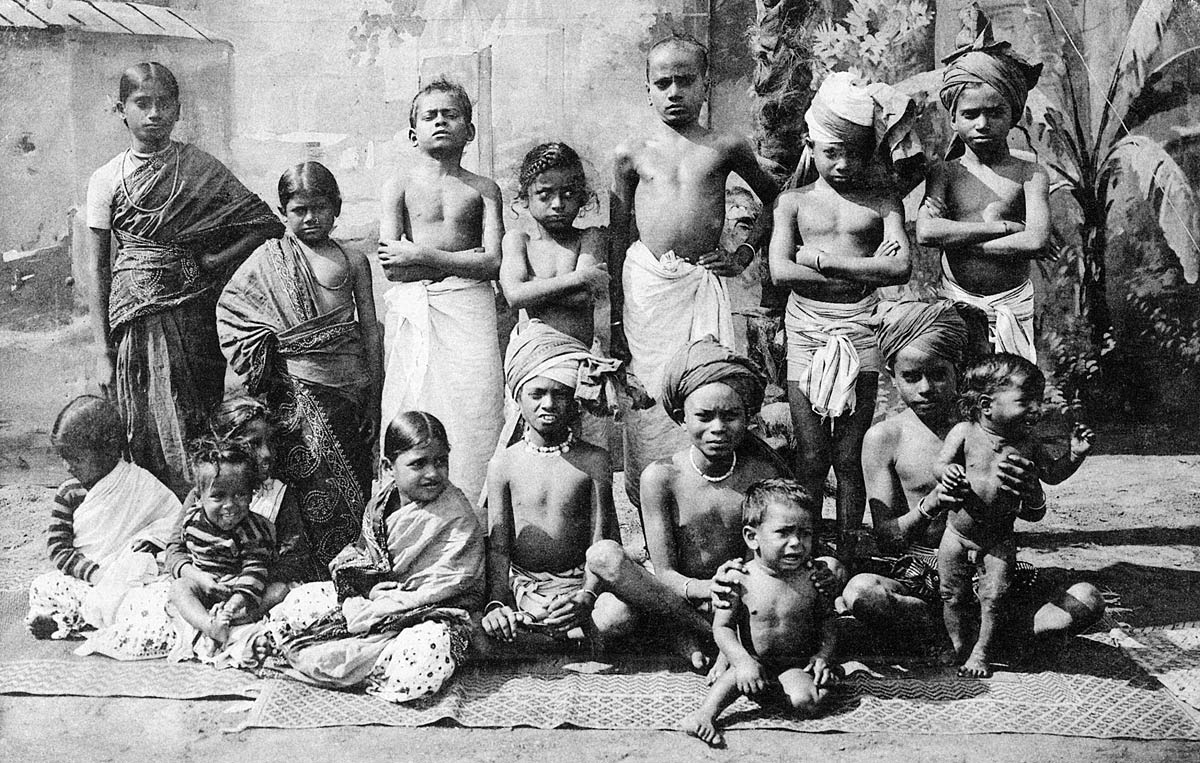

In the book Carl Hagenbeck's Empire of Entertainments by Eric Ames (2008) he describes the importance of this exotic showman and his family who helped turn "India" into a touring spectacle following an 1898 exhibition in Berlin, even if most of the performers were Tamils from Sri Lanka where his two step-brothers were based. Ames writes:

"In the context of ethnographic exhibition, the name helped organize a diversity of offerings in a way that spectators could readily identify and understand. It also announced the troupe’s country of origin. In this instance, however, the location was embedded within the brand’s name, which in turn had certain implications for the display. Most remarkably, the construction of theme space here was indistinguishable from the promotion and expansion of the brand. Customers paid to visit neither India nor “India,” but rather “Carl Hagenbeck’s India.” Headlining the publicity materials and almost all the signage throughout the showground, the brand name featured more prominently than the context of origin. Branding an entertainment with a name such as “Carl Hagenbeck’s India” promised certain benefits to spectators, while establishing an imaginary bond between the audience and the show’s sponsor. In addition to an exciting show, it promised such intangibles as quality, reliability, authenticity, and respectability. To project and maintain a strong brand image was to bolster, on a sub-representational level, the entertainment’s perceived quality and internal coherence. The themed environment became an increasingly commercialized space, in part due to the strong identification and mutual reinforcement of the brand and the entertainment.

"The Hagenbeck brand became a kind of platform on which he and other members of the family could introduce new products, entertainments, and related merchandise. Indeed, one indication of the brand’s strength and resilience was the extension of “Hagenbeck,” beyond the animal trade and the Volkerschau, to other categories like the circus and the zoo or to perishable goods such as tea and tobacco. On the one hand, each extension meant for consumers repeated expressions of the brand and repeated experiences with Hagenbeck’s notion of the exotic" (p. 117).