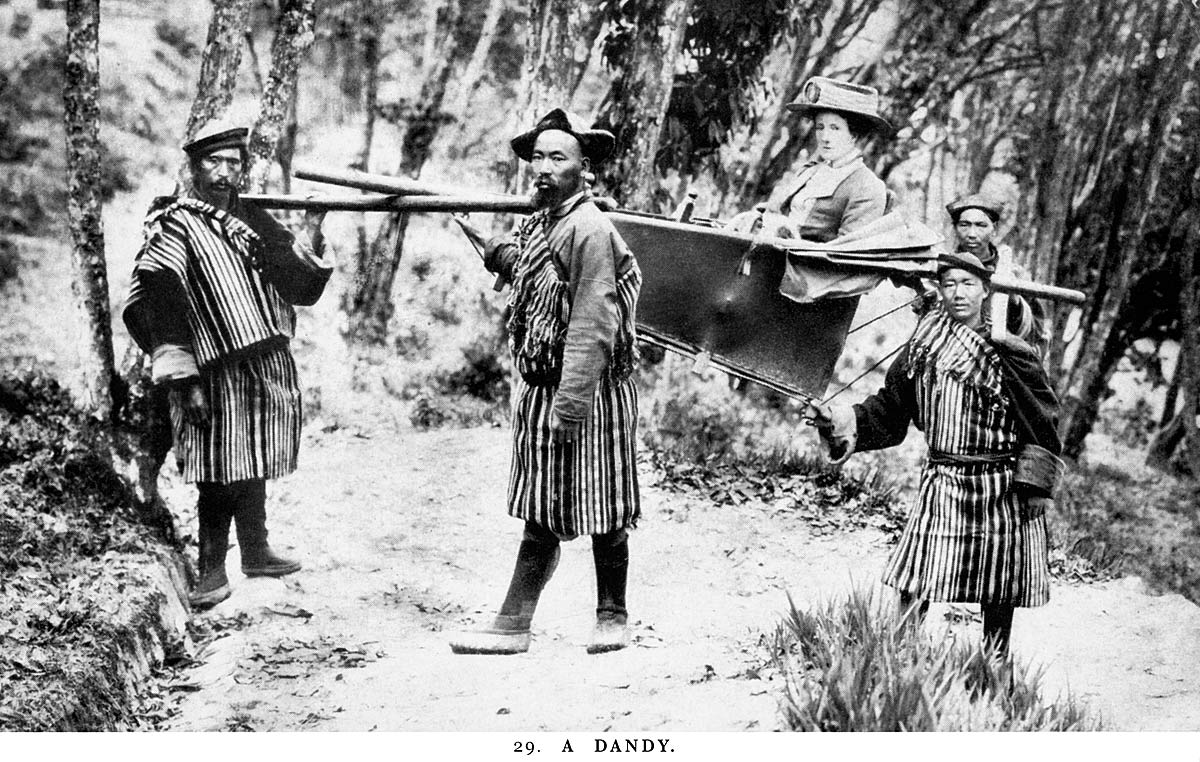

"I was carried to and from the hall in a primitive conveyance, called a “dandy”; it consists of a bit of canvas, fastened stoutly to an oblong frame of wood, terminating in a short pole at either end," writes Margaretta Catherine Reynolds, author of the fine memoir At home in India ; or Tâza-be-Tâza (1903). "The canvas forms a kind of hammock, in which one sits, being carried by the poles on the shoulders of two bearers, four of whom accompany each dandy; this mode of locomotion being by no means unpleasant."

Another point of view, as Clare Danes notes in the book Transcultural Encounters in the Himalayan Borderlands (2017) writing about precisely this Paar postcard, refers to Saloni Mathur as seeing in "the white woman carried aloft in a dandy by local men, the 'natives' are literally the bearers of European civilisation embodied, in this instance, in female form" (p. 100).

The word dandy itself, according to Hobson-Jobson, has multiple meanings, from a boatman in Gangetic rivers, with an origin in the Bengali dand, 'a staff or oar,' to a type of ascetic who carries a small wand or Dand. For a third meaning, the dandy pictured here, they write: "Same spelling, and same etymology. A kind of vehicle used in the Himālaya, consisting of a strong cloth slung like a hammock to a bamboo staff, and carried by two (or more) men. The traveller can either sit sideways, or lie on his back. It is much the same as the Malabar muncheel (q.v.), [and P. della Valle describes a similar vehicle which he says the Portuguese call Rete (Hak. Soc. i. 183)]. [1875. -- "The nearest approach to travelling in a dandi I can think of, is sitting in a half-reefed top-sail in a storm, with the head and shoulders above the yard."-<-> Wilson, Abode of Snow, 103." (p. 296). One stick, many worlds.