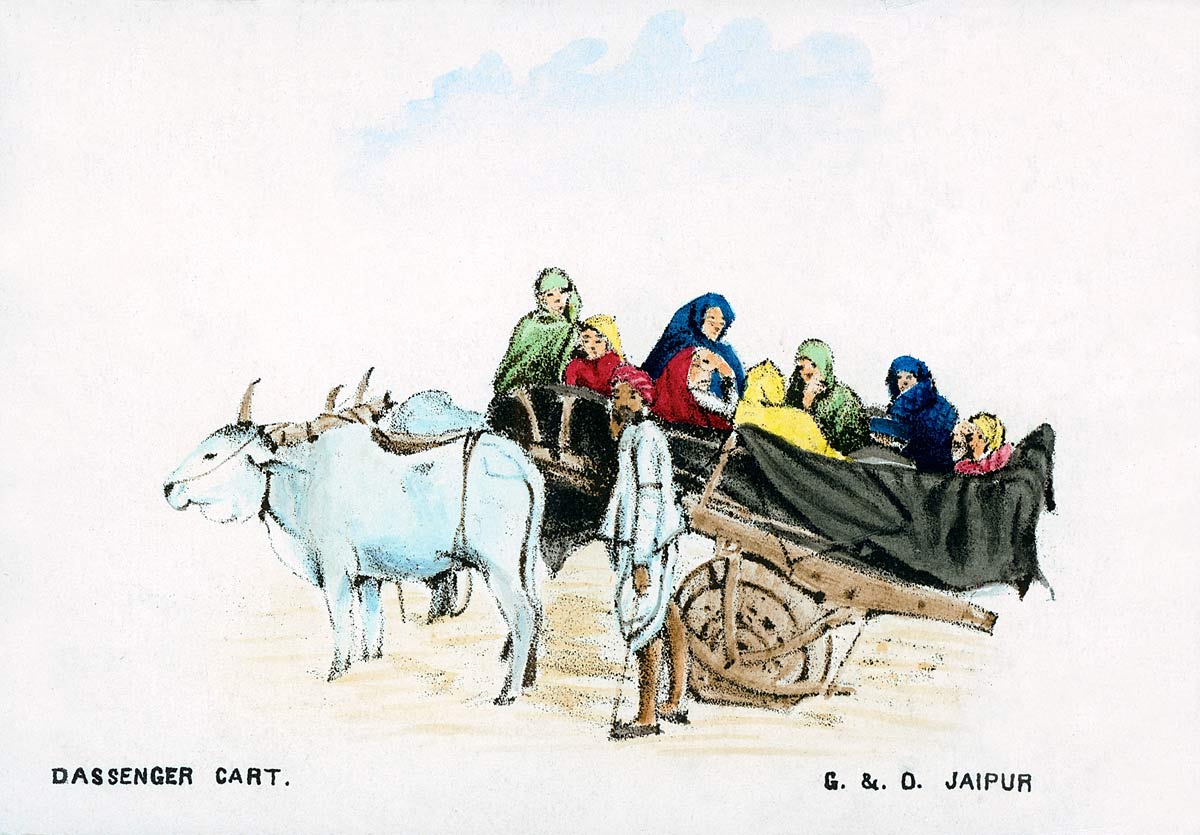

A very early lithographic postcard by Gobindram Oodeyram that seems to have been printed in India. A compelling glimpse of the rural poor in the sprawling state of Rajasthan during what were trying times. In 1900 for example, just as the plague debilitated Mumbai, an unrelated famine claimed ten percent of Jaipur’s population of 160,000. The French writer Pierre Loti, who passed through Rajasthan by train at the time wrote "At the first village at which we stop a sound is heard directly the wheels have ceased their noisy clanking–a peculiar sound that seems to strike a chill into us even before we have understood its nature. It is the beginning of that horrible song which we shall hear so often now that we have entered the land of famine. Nearly all the voices are those of children, and the sound has some resemblance to the uproar that is heard in the playground of a school, but there is an undefined note of something harsh and weak and shrill which fills us with a sense of pain.

"Oh! look at the poor things jostling there against the barrier, stretching out their withered hands towards us from the end of the bones which represent their arms. Every part of their meagre skeleton shows with shocking plainness through the brown skin that hangs in folds about them; their stomachs are so sunken that one might think that their bowels had been altogether removed. Flies swarm on their lips and eyes, drinking what moisture may still exude. They are almost breathless and nearly lifeless, yet they still stand upright and still can cry. They are hungry, so very hungry, and it seems to them that the strangers who pass by in their fine carriages must be rich, and they will pity them and throw them something.

"'Maharajah! Maharajah!' all the little voices cry out at once in a kind of quivering song. There are some who are barely five years old, and these, too, cry 'Maharajah! Maharajah!' as they stretch their terribly wasted hands through the barrier.

"The Indians who are travelling in the train are only humble occupants of the third and fourth classes, but they throw what they have, scraps of cake and copper coins for which the children rush like wild beasts, trampling each other under foot. What use can they make of the money? It seems that there is yet food in the village shops for those who have money to buy it with. Even now there are four wagons of rice coupled to the trains behind, and loads pass daily, but no one will give them any, not even a handful, not even the few grains on which they could live for a little while. These wagons are going to the inhabitants of those towns where people still have money and can pay" (Pierre Loti, India, 1906, p. 172).

Passenger Cart

c. 1902

13.00x

9.10cm